|

Originally published on The Huffington Post As the bus drove through Plovdiv's suburbs, after a two-hour journey from the capital Sofia, I felt like I was visiting an old friend. I have had an inner obsession with Plovdiv for years. My fixation with the myth of Orpheus led me to the lands of ancient Thrace, right to this historic city situated between the Rhodope Mountains (the legendary homeland of Orpheus), the Thracian Plains and the Balkan Mountain Range. The sun already burned in May, amplifying the car fumes in the Hristo Botev Boulevard as we made our way from the bus station, and even finding our hostel became an adventure. The street signs sprawled in Cyrillic script fortified the impression of being on the "other side of Europe". The road curved past the tall chestnut trees shading the street, under the flaking houses that paved the way to our guest house. On first impression, Plovdiv was slightly dilapidated with a sense of fading grandeur, a quality I love in old cities. I adored Plovdiv instantly, but the best thing was that I knew there was more to discover in the hot and dusty streets of Bulgaria's second city. Hills peeked up above flaking façades adorned with elaborate plasterwork. The city had seven hills once, like Rome, but they were used as quarries over the centuries, leaving the city with only five, maybe six hills that can be classed as such, where the three hills of the old town are the most prominent. Plovdiv's history dates as far back as 4000BC, when it began life a Neolithic settlement. It is one of the World's most ancient cities and Europe's oldest inhabited city -- even beating Athens. The settlement was originally Thracian, but it became a major Greek and then a Roman city known as Philippopolis, named after the King of Philip II of Macedon, Alexander the Great's father, who conquered the city in 342BC. Plovdiv became a city in tune with the ever-changing evolution of history. Echoes of Plovdiv's past still wink behind fenced off excavation areas in the center, hinting at Roman columns and overgrown Thracian ruins on the hillside. The narrow streets of the city's Revival era old town coiled up the hill, taking us up, across the large stone clad pavements radiating the heat as we sweated up the hill searching for the city's history. Our base instincts took us down the most shaded roads, leading us into Plovdiv's Roman Theater. The Theater overlooks the city, with views all the way over to the Rhodope Mountains that span the southern fringe of Bulgaria and all the way into Greece. There were no crowds here, just a couple of people scattered about the marble stones and the towering colonnade of the reconstructed stage. Encased with a fence of metal bars, a rope cord stretched across a gap, marking the entrance to the Theater. The ticket collector sat under the shaded veranda enlaced with flowers and vines only meters away. I handed over 5 Lev (2.50€) to the ticket collector as a cat brushed my leg. I caught sight of another tabby ducking under a bush by the ring of worn down marble seats. "Too many cats," he said to me, "I look after all of them. I have five at home and about twelve here. But, someone has to take care of them." He pointed to a sack of dry cat food, but I didn't catch sight of any of Plovdiv's "Roman Cats" for the rest of the afternoon. I could only make out a hum of distant traffic as I walked through Plovdiv Old Town's deserted streets. I found it surreal, and refreshing, to stroll through a city as beautiful and as historically significant as Plovdiv, without encountering endless shops selling tat for tourists or restaurants where determined waiters try to drag you in. I caught the scent of lilacs and the subtle background noise of crockery behind opened wooden shutters. Most of Plovdiv's touristic life takes place on Saborna Street, but even here the gift shops retain a sense of authenticity, like the artisanal gallery, whose painted antique carts and ploughs filled its courtyard. Further down, just before we reached the gold and black sinuous waves of Plovdiv's Ethnographic Museum, a live chicken clucked at us from the top of a postcard stand, just outside a souvenir shop in the square. Ancient Plovdiv is subtle, especially when the elaborately painted houses decked with wooden beams from the Bulgarian Revival hog the limelight, albeit deservedly. Roman ruins are always in the undergrowth; some are excavated and beautifully presented, like the Theater or the Stadium in Plovdiv's busy downtown. Plovdiv's Thracian heritage shies away up on Nebet Hill, where its overgrown ruined walls overlook the Old Town and the Mosque. I didn't expect to find the Orpheus connection in this Thracian city, I had plans to pursue that obsession in the Rhodope Mountains the next day. Yet, as I descended the steps from the Old Town, I caught sight of a mural towering above the creeping ivy, shrubbery and graffiti covered wall. With a lyre in hand, etched into the side of an old house - I found Orpheus.

0 Comments

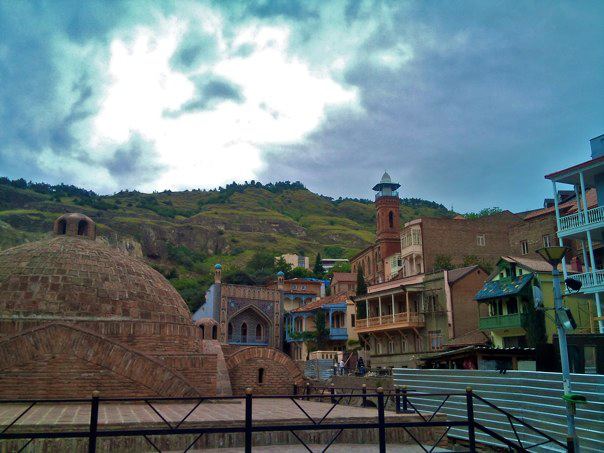

The Georgian capital of Tbilisi has been all over the travel news today, and for all the wrong reasons. A post on CNN’s travel page, “Redeeming sights in the world’s ‘worst cities’“, offered a promising article showcasing “pleasant” images from the World’s supposed “worst cities”. It was an interesting idea, in theory, but in addition to the article’s questionable writing, its inclusion of Tbilisi, Georgia has inspired a lot of anger and annoyance out there, not only among Georgians, but foreigners too – myself included. In 2012, I lived in Tbilisi. In fact, I almost moved there permanently, but my job at the newspaper didn’t work out, plus I was homesick for my friends back in Madrid. However, it wouldn’t be honest of me to say the city is perfect: it isn’t. My electricity cut out for 12 hours a day at least once a week, my kitchen flooded twice, on occasion I didn’t have working water and I even got poisoned by drinking the tap water during my first two days in Georgia. And, don’t get me started about being a pedestrian in the city, that’ll just branch out into another rant. Yet, in spite of the above, Tbilisi will always hold a special place for me. Here are some reasons why Tbilisi should not be on CNN’s worst cities list. 1. The Architecture I love Tbilisi’s architecture, I could write pages and pages about it. It is a city with a long and complex history, and this shows in the eclectic mix of buildings that draw from European and Asian elements. I adore the contrast of the lapis lazuli coloured tiles of the Orbeliani baths, which sweep me away into ancient Samarkand and Persia, against the galleried houses taken straight out of New Orleans’ French Quarter (or is it the other way round?). Tbilisi also has its own brand of art nouveau architecture. Even in the dilapidated backstreets of the Sololaki neighbourhood, each building, especially those being consumed by hungry vines, has its own story to tell. Up in Mtatsminda, the paint flakes from formerly decadent apartment blocks, whose dusty hallways invite me in to explore. 2. The Food I still have dreams about khinkhali, slippery boiled dumplings stuffed with a spicy meat filling and its juices. I used to pay 2.50€ for five pieces at a hole-in-the-wall near my house, which satisfied both my taste buds and my hunger. Khachapuri, a Georgian cheese bread filled with a local tangy cheese, it’s rich, it’s delicious and it’s a heart attack on a plate, especially the Adjaran Khachapuri – which comes topped with a whole egg and slivers of butter. It’s a symphony in the mouth, but you can feel your arteries clogging up as you eat it, and it’s best left for the days you plan to climb a mountain or two. You can also find a bean stew known as lobio, which is perfumed with coriander and fenugreek, and shashlik, a marinated Georgian kebab. Each meal is a feast in itself and must be washed down with a healthy portion of Georgian wine, which brings me to… 3. The Wine Georgia is the birthplace of wine, with a history of vini and viti-culture going back to at least 6000 years, if not more. Wine is an integral part of Georgian culture, and it’s still produced to this day using the ancient method of fermenting grapes in Qvevri, amphora-type terracotta pots that are buried in the ground for 6 months. White wines are made by using white grapes, but without removing their skin the way Western wine making practices do, giving them a tannic quality and a full body. Georgian wine is unique, and I sorely miss it now I’m back in the land of Rioja and Ribera. 4. The People Georgians are some of the kindest people I’ve met in my travels and they’re willing to go without if it means helping a guest. My landlady came to the airport at 5 a.m. when I flew in from Spain to take me to the apartment, and when I left Georgia, an art historian, whom I interviewed for an article, paid for my taxi to the airport. In Georgia, people are always there to help you, they smile at you and say “gamarjobat,” hello, when you pass them in the street. My friends broke down in their rental car in the Caucasus Mountains and within minutes they were helped out by passing locals. 5. Culture I’m an art columnist based in Madrid, Spain, so you can imagine I have high standards when it comes to cultural expectations. After researching Tbilisi’s art history, my fascination with the country grew. In the early 20th century, Tbilisi was the “third city of culture” after Paris and Moscow. Artistic circles sprung up around the city with a collective of artists, poets, writers and actors. Artists from Georgia’s avant-garde went to Paris and hung out with the likes of Picasso and Duchamp. You can see paintings by Pirosmani and Kakabadze, or visit the golden treasures from ancient Colchis at the archaeological museum. Tbilisi has a brilliant classical music scene, along with jazz, and not to mention the film, theatre, music and folk festivals. 6. Safety As a single Western woman, before I went to Georgia I was concerned about getting harassed and hassled. Plus the fact Georgia was only at war with Russia a few years back had also unnerved me. During my stay though, not once did I feel unsafe, even when I was out alone at night. In Tbilisi, people leave their doors unlocked, trusting that people won’t rob them. Tbilisi’s crime rate is very low, and while the risk of getting run over by a car or a marshrutka, a local minibus, is high, in general the city is incredibly safe. 7. Public Transport Tbilisi has an efficient, modern and clean metro line, which is more than I can say about Rome. While there are only a couple of lines, it’s fairly easy to negotiate about the city with the metro network, and there is a wide range of buses too. Tbilisi might have its flaws, but I definitely would not lump it in with the likes of Khartoum and the other Sub-Saharan cities on the list. The article on CNN is misleading and gravely wrong in many ways. Tbilisi is NOT one of the worst cities in the world, and it definitely has more redeeming features than its Abanotubani, bath, district.

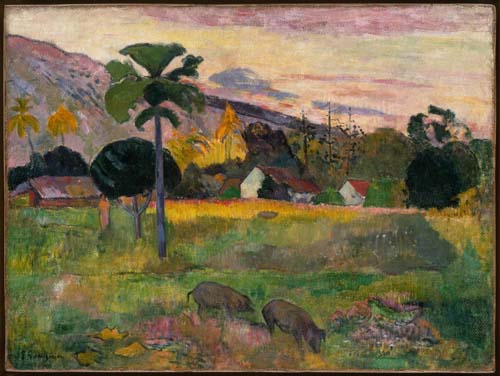

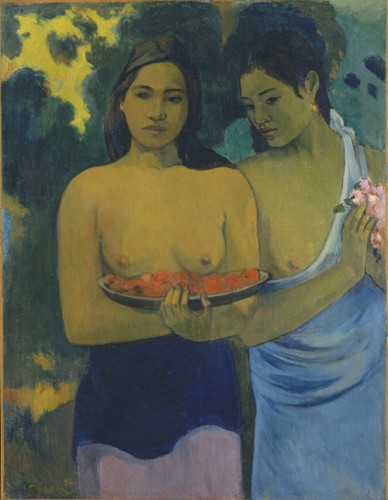

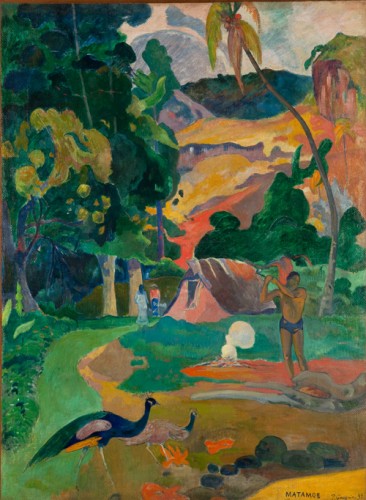

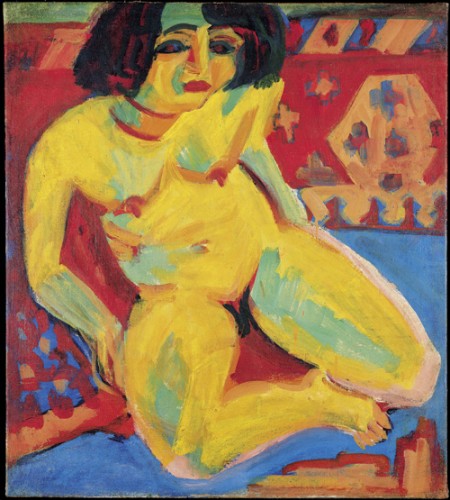

*I'm undertaking a course in travel writing with MatadorU, and this was one of the assignments we had to do on travel narratives - where you have to immerse yourself in the story.* My heels click down the abandoned Calle Echegaray, only a few blocks from Madrid’s chaotic Puerta del Sol. Houses line the narrow street with flaking façades illuminated by hanging streetlamps. The road curves in at the centre, channelling the rainwater into a thin stream between the tiles. The panelled wooden doors of La Venencia are open and I catch a whiff of musty, damp barrels and cold cuts of meat. The walls are yellowed from the decades of cigarette smoke, even though today’s smokers are forced outside into the rain. Stripped bits of white plaster show through the brown ceiling, and dogged-eared vintage posters advertising sherry are pinned up around the walls. It seems to me that La Venencia has hardly changed since the Spanish Civil War, with the mahogany bar, tables and chairs fading into uneven patches of brown. It’s cold inside and minutes after opening time on a Sunday night, we’re only five: three locals, the bartender and me. I’ve been coming here for years, but I’m still self-conscious about my “guiri,” the Castilian word for foreigner, status, with my pale skin, blue eyes and hybrid British-Eastern European accent. Even with my correct use of the Spanish subjunctive it’s obvious I’m not local. “One palo cortado, please,” I ask. The bartender places a glass of “palo cortado,” a caramel coloured sherry on the wooden counter. I sip from the tulip shaped glass, the heavy legs trickle down the sides and the sticky fluid leaves my mouth with the sharp taste of dried fruits. Lubricated with alcohol, I attempt conversation, resorting to the icebreaker us Brits always fall back on. “Que hace frío, no?” I say, “It’s cold.” “Sí, the problem is the damp,” he replies with a deep, gruff voice and scribbles down the price of my sherry in chalk on the wooden counter. He avoids making eye contact with me and turns towards to a local and I’m thinking about how to get in on the conversation. Voices echo around the bar, highlighted by the emptiness of a place which is usually packed full. “It’s very quiet tonight,” I say. My eyes stare up behind the bar to the endless rows of sherry bottles of varying brands, shapes and sizes. They’re all covered in dust, fitting in with the flaking décor of the bar itself. “Sí,” grunts the bartender and raises his shoulders. He taps chalk dust on his dark green apron that he’s wearing over red and white checked shirt that suits his leathery complexion. “It’s Sunday and Spain is in a crisis, what do you expect?” The first time I came into the bar he yelled “no photos,” at me; returned my change, and gesticulated to the piece of paper stuck on the wall that says “no tips.” La Venencia hasn’t shaken off its habits from the Civil War and its memory of Franco. When Hemingway hung out in this bar gathering information as a war correspondent, anonymity and proletarian solidarity were matters of survival. A woman taps me on the shoulder and says, “Your scarf is on the floor”. She sides up to the bar and brushes her dripping black hair from her face. “Antonio, give me an amontillado,” she says, “It’s raining ‘cats and dogs’ out there.” I glance up to the tables in the upper part of the bar as they fill up. A mangy, longhaired black cat struts down the tiled steps. On my first visit, I mistook her for someone’s fluffy handbag until the golden eyes flashed back at me. Tonight, she comes to my table and jumps onto my lap. “She likes you,” says the woman, “she’s normally not that friendly, she only sits on the laps of a couple of locals.” She’s clean, however her fur is slightly matted. She’s curled on my lap with no sign of budging. “What’s her name?” I ask and cautiously stroke the cat. “Lola,” says the woman, “She’s quite old, she’s been living here at the bar for years.” A young man walks in and shakes his umbrella, the water droplets land on my notebook and me. Lola the cat jumps up and scuttles off to the other side of the bar, and curls up next to an empty sherry bottle. I get up and go to the bar. “Can I get a manzanilla please, and a tapa of cheese and salchichón.” I ask the bartender. “Do you want some olives too?” he asks. His tone is softer than before. I look up and smile, “Yes, please,” I say. “OK,” he scribbles the amount down on my tab at the bar, the corner of his mouth curls up — do I detect the hint of a smile?  This article was previously published on My Vacation Source. If there is one thing Madrid doesn’t lack – it’s bars. The neighborhood of Malasaña alone contains one bar per seven people; so going out on a pub-crawl in the Spanish capital requires minimal effort. But what if you want to do something a little different? Like walking in Hemingway’s footsteps, while eating and drinking along the way. Hemingway described Madrid as “the most Spanish of all cities.” He arrived in the early 1920s and maintained a presence in the city up until the 50s, only leaving Spain during the Axis allied 1940s. Hemingway’s long-term residency in Madrid means that you can pretty much walk into any bar in the centre dating the pre-1950s with some connection to the writer. There is even the urban legend of a displayed placard outside a restaurant that says, “Hemingway never ate here.” For those who like to fuel up before a night of drinking, why not enjoy a meal at El Sobrino de Botín, just off Plaza Mayor? With claims of being the “oldest restaurant in the world,” El Sobrino de Botín is also featured in the final scenes of the “Sun Also Rises.” This antique dining establishment offers a three-course menu including garlic soup and suckling pig. While this classic set menu may not cater to everyone’s tastes, there is also a la carte menu available. If the suckling pig offered at El Sobrino de Botín seems a bit on the heavy side, or you’re partial to tapas, Spanish snack food, then you can have a bite to eat at the next port of call – Cervecería Alemana. The American writer’s old haunt can be found at end of the Plaza Santa Ana, and according to Hemingway, supposedly, serves the “best beer in Spain.” Cervecería Alemana can be described as a German beer hall meets a Spanish tapas bar, with its wooden beams and white walls combined with the noise and chaos you can only find in Spain. They serve a variety of international beers, but the house beer is most excellent. Served in a white mug that matches the head, it echoes the bready wheat beers from Germany, while still maintaining a light taste. This bar is an even mix of tourists and locals, with grumpy waiters rushing around taking forever to note your food order. This manages to work as part of tavern’s charm, though. Hemingway frequented the Cervecería Alemana often, so much so, that he “owned” the small marble table right next to the window. Although the current owners claim that Hemingway was intensely disliked by the proprietors in his time. The next stop on the agenda is the hidden bar of La Venencia. Only a five-minute walk from the popular Plaza Santa Ana, Calle Echegaray is quiet and can even seem a little abandoned at night. Keep walking down until you come to a pair of wooden shutter-like doors that mark the entrance to the bar. Back in the 30s, Republican soldiers and sympathisers during the Spanish Civil War used to meet here. As a war correspondent, Hemingway would hang out here for news on the front. If sherry isn’t your thing then La Venencia won’t be for you – because, apart from tap water, that’s all they serve. Good news for sherry lovers though, is that they have five different varieties from the barrel, available full or half bottle sized or even by the glass. If you’re still after something to munch, you can find tapas that perfectly accompanies sherry at very low prices. La Venencia is covered with vintage posters and the walls are yellowed with cigarette stains. The bottles on the top shelf haven’t been dusted since, well, when Hemingway was last there, most probably – but it’s part of its appeal. Mostly locals crowd the bar, and you can still see the sign from the Civil War that says “Don’t spit on the floor.” Not only that, La Venencia has maintained some of its republican traditions from Hemingway’s time, such as the rule about no photographs – a safety precaution against Fascist spies, and no tipping. The latter might sound strange, but these were socialists and workers. From the gritty Republican hangout of La Venencia, Hemingway also found himself in the elegant and fashionable Taberna Chicote, now appropriately renamed Museo Chicote. Situated on the Gran Vía, considered the height of modernity back in the early 1930s with its grand, art deco buildings and lively theatres, Taberna Chicote proved to be popular with international journalists at the time. Hemingway wasn’t the only famous face to have passed through this chic bar. Its former customers included Grace Kelly, Orson Wells, Laurence Olivier and even Salvador Dalí. Nowadays, thanks to its legendary reputation, Museo Chicote still offers a variety of classic cocktails at not unreasonable prices. It marks the perfect end to the Hemingway pub-crawl – sitting in its classy, art deco setting almost transports you back to the glittering 30s with a cocktail in the hand. While three bars hardly constitutes a pub-crawl, the combination of foamy beer, sherry from the barrel and classic cocktails is a lethal mix that Hemingway would be proud of. As long the tapas and tap water keep flowing, there is no reason why not to make the most of this trip down Hemingway’s memory lane. So grab a copy of the “Sun Also Rises” and have a drink with Hemingway! Information: El Sobrino de Botin Calle de los Cuccilleros 17 Tel: 0034-913664217 (Reservation recommended) Website: www.botin.es Cerveceria Alemana Plaza Santa Ana 6 Tel: 0034-914297033 La Venencia Calle Echegaray 7 Tel: 0034-914297313 Museo Chicote Gran Via 12 Tel: 0034-915326737 Website: http://www.museo-chicote.com/  Only a few days left to see this stunning exhibition (finishes on the 13th of January 2013). Go while you still can! Originally published on Kunstpedia. Running away to escape his Parisian demons, Paul Gauguin sought refuge in his very own paradise lost in the exotic surroundings of Martinique, Tahiti and the Marquesas Islands. Through Gauguin’s voyage to primitive lands and an explosion of colour, modern art finally received the revitalising injection it desperately needed under the stagnant European skies. Coinciding with the 20th anniversary of the Thyssen-Bornemisza museum in Madrid, the exhibition “Gauguin and the Voyage to the Exotic” follows the artist’s journey to Tahiti, exploring his artistic transition into primitive and authentic worlds where his palette experienced an explosion of colour and expression. However, the carefully curated exhibition by Paloma Alarcó at the Thyssen-Bornemisza goes beyond Gauguin’s Tahitian landscapes, but analyses the effect the French artist had on the world of modern art exploring the effect primitivism and colonialism had on movements such as the expressionists, fauvists and on abstract art. The display at the Thyssen-Bormemisza is split into three themes with eight overall sections. Firstly, Gauguin is studied as a figure in his own right and introduces his seduction by the virginal and unspoiled lands of the tropics. As an artist, Gauguin’s paintings from the South Seas are among some of the most sensual and alluring images that can be found in modern art, not to mention the influence his work exerted on artists like Matisse, Kandinsky and many others. The exhibition also examines Gauguin’s voyage into the exotic as a means to escape civilisation. This is a key turning point, not only in the artistic and personal career of Paul Gauguin, but within the context of avant-garde’s primitivist revival, linking into the final theme: the modern concept and its treatment of the exotic by linking back to ethnography. The invitation to the exotic didn’t begin with Gauguin, the French artist Eugène Delacroix sought inspiration on the shores of North Africa, where his orientalist depictions of Arab women and scenes from Algerian life were to inspire wanderlust in a young Gauguin. A sensually exotic scene by Delacroix of “Women of Algiers in their Apartment (Femmes d’Alger dans leur intérieur)” painted in 1849 opens the exhibition, with Gauguin’s Tahitian scene “Parau api (What’s New?)”, mirrored besides it. Looking at the paintings side-by-side, we observe the impact Delacroix’s North African paintings had on Gauguin. “Parau api (What’s New?)”, depicts a pair of women reclining on a canary yellow backdrop, whose poses mimic the Algerian women in Delacroix’s scene. Before Gauguin’s iconic Tahiti, there was Martinique. While Gauguin’s time in the Caribbean was brief, its effect on his artistic development was intense. Martinique was the first time the artist used the tropics as his muse, where the landscape and the local people would forever modify his pictorial language. In Gauguin’s Martinique paintings, his form is still underdeveloped when compared with his later Tahitian works. The composition of the artist’s paintings from his Caribbean period drew from Cézanne, with their long and oblique brushstrokes, bestowing his paintings not with the clear brilliance of his later works, but with a vibrant, if not rough, texture in his canvases. His painting, “Coming and Going, Martinique” from 1887 is a good example of this style. We see the effect the exotic had on the artist’s work, yet his palette is dulled and less daring than his later paintings, but it marks the beginning of a new era for Gauguin. When he travelled to Martinique, Gauguin was accompanied by his friend Charles Laval, whose work is displayed side-by-side in the exhibition. We can see in Laval’s Martinique landscapes that he shared Gauguin’s decorative brushstroke application. Gauguin’s time in Tahiti was the creative peak of the artist’s life. His time on the South Pacific island allowed him to focus on the rich local culture and the brilliant nature that surrounded him, bringing out a synthesist style that was based on large areas of brilliant colour. In Gauguin’s Tahitian paintings, colour conveys meaning, as Gauguin begins to treat his palette as form of emotional expression. It’s not only his thoughts and feelings that are communicated on canvas through the bright colours, but they are also rich in symbolic content. The display showcases some striking examples of Gauguin’s Tahitian paintings, most notably, “Mata Mua (In Olden Times),” “Two Tahitian Women,” “Matamoe, Death. Landscape with Peacocks.” His paintings are nostalgic, depicting a “Paradise Lost” of an innocent and ancient world dying in the advent of colonialism. However, it’s not just the outside world that darkened Gauguin’s own tropical paradise. Gauguin was suffering from late stage syphilis, which caused deterioration in both his mental and physical health, transforming his paintings into darker and more sinister compositions – blurring the boundaries between his Tahitian paradise and personal hell. Up until now, the exhibition mostly focussed on Gauguin’s own travels and creative development. “Beneath the Palm Trees,” commences an examination of the artists who found inspiration in Gauguin’s exotic journeys. The theme of the jungle became a new source for the avant-garde artists to tap into, giving modern art the desperate injection of new ideas it needed after a crisis that wasn’t just aesthetic, but a moral and political one also. Gauguin played a crucial role in the transformation of modern art. If we examine Gauguin’s own interpretation of symbolism, whose analogy married art to the dream world, Gauguin manages to transport that into a self-contained fantasy. By combining the primitive and savage worlds of the South Pacific with his own symbolist ideals, Gauguin grew creatively as an artist through his relationship with untamed nature, and whether their inspirations were real or imaginary, many artists followed suit. The wild and the savage offered a path to innocence that appealed to the artists of the early 20th century, where childish regression became mirrored in contemporary art. Gauguin’s exotic resonated to an obvious extent with artists like Rousseau and Matisse, among others, but Picasso found artistic companionship with the exotic and childish primitivism. Picasso might have found inspiration through African art or the primitivist paintings of the Georgian painter Niko Pirosmani, but he still searched for this child like innocence from outside of his own cultural sphere in the same manner as Gauguin. Artists whose work clearly show direct influence from Gauguin are seen in the exhibition, Henri Rousseau’s “Tropical Landscape: An American Indian struggling with a gorilla,” echoes the symbolist landscapes from Gauguin’s Tahitian scenes, Emil Nolde’s palette is a tribute to the bold colours of the French emigré artist, and Ernest Ludwig Kirchner and Otto Müller’s nudes evoke the exotic sensuality of Gauguin’s paintings of Tahitian women. Ethnography became a popularised trend in the early 20th century, as more artists discovered a new way of viewing the world thanks to Gauguin’s contribution to modern art. The French fauves and the German expressionists grew from Gauguin’s artistic gaze to seek out the different and the “Other.” To fauvism, expressionism and Russian primitivism, Gauguin will remain the artist who set out into the wild in search of a new vision, who became a canon to a whole new generation of artists, whether they took to the exotic in ethnographic museums or went on their own voyages. We can see his influence in displayed works by Mikhail Larionov’s “Blue Nude,” Henri Manguin’s “The Prints” or Kirchner’s nudes. Many avant-gardes explored countries closer to home, such as North Africa, in search of a new pictorial language of light and colour. Kandinsky’s oil paintings are early works that are uncharacteristic of the abstract artist, but show a growing interest in space, colour and form inspired by Tunisian scenes, although we begin to see the brilliant use abstract forms combined with colour that take shape in his later works. The same is seen in the paintings by Paul Klee and August Macke, whose abstract forms a far from Gauguin’s symbolist paintings, but attribute their palette and exotic themes to the artist. The exhibition concludes with Matisse and F.W. Murnau’s journey to Tahiti. Matisse’s bright, brilliant colours and primitive lines stem from Gauguin’s influence, but in 1930, Matisse also sought inspiration in Polynesia, coinciding with the production of the film by the German expressionist director F.W. Murnau, “Taboo: A story of the South Seas.” Matisse’s journey to Tahiti was for pleasure, and while he painted and drew landscapes and portraits of the actors from Murnau’s film, Tahiti moved his work into an alternative view of the island. Matisse’s perspective is different, and his Tahitian paintings lack that same raw creativity Gauguin found in his lost piece of paradise. Gauguin escaped civilisation, throwing himself into the Tahitian world that impacted art in a way that was no longer sophisticated or decadent. It consumed him, inside and out, and left a huge mark on the art that secured his succession and artistic legacy.

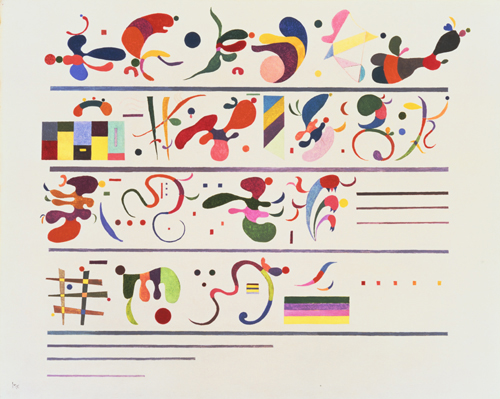

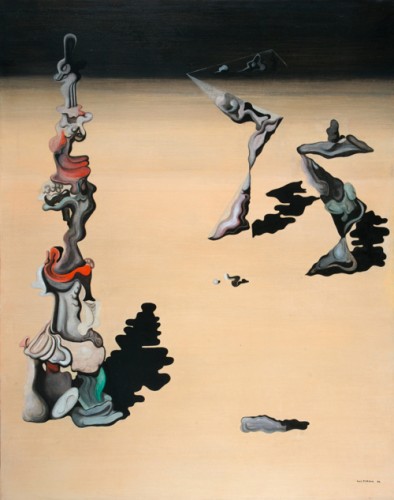

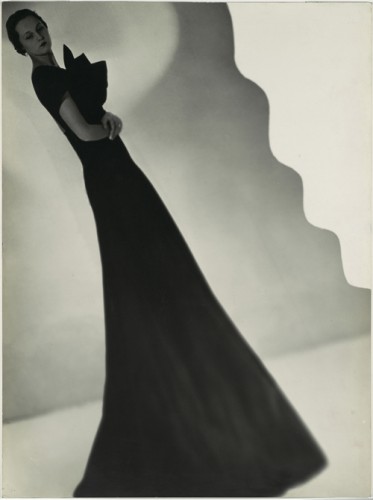

Eastbourne is one of the iconic British seaside resorts you'll find scattered along the East Sussex coastline. For a long time, I never really understood the appeal of my hometown* as a holiday destination. Eastbourne is Brighton's frumpy sister and is dubbed by many as "God's Waiting Room" due to the large number of old peoples' homes. While going home to Eastbourne doesn't fill me with excitement after having lived in Budapest, Frankfurt, Madrid and Tbilisi, slowly I'm beginning to see the quirky appeal of this little seaside resort. The town is undoubtedly picturesque, with its Edwardian architecture and sea views. This is classic "Sussex by the Sea" territory: it's antique, and it's not the fashionable, up-dated version you'll find in Brighton. People flock to the shingled beaches at the first ray of sunlight with a box of takeaway fish and chips, while predatory seagulls shriek in the air plotting their culinary burglary. My personal impression of Eastbourne is its grittier, chav laden side of inebriated girls tottering around in miniskirts or the drug dealers who sit on the street corners in the residential areas behind the seafront. However, after taking a stroll along the seafront on a very sunny New Years Day allowed me to gain new appreciation for the town. Away from the derelict back streets you'll find a town that's full of old fashioned charm. Often I've had to bite my tongue from laughing at the signpost "The Sunshine Coast Welcomes You." It's always raining when I pass it, but statistics show that Eastbourne has a track record for the highest levels of sunlight in the UK (although, I think another town has stolen Eastbourne's sunshine crown now). This is a bit depressing when you think about it, especially since it's already dark by 3 p.m. in December. On the rare occasion when the sun is out, Eastbourne is very pleasant. Walks along the seafront are refreshing. There are plenty of cafés along the beach, which make for a nice spot for a coffee with a sea view or if you're looking for something more traditional, you can enjoy a cream tea on the pier. For the more adventurous walker, there is a picturesque hike up to Beachy Head. This is famous for being one of the top suicide spots in the world, but the white cliffs around Beachy Head offer some of the most stunning coastal views in the UK. Despite Eastbourne's unfashionable image, you'd be surprised at the number of celebrities who've passed through the town. Apparently, John Malkovich even owns a hotel here and has been spotted on the seafront a few times. Eastbourne has had its fair share of famous visitors and residents. Charles Dickens performed amateur dramatics at the Lamb Theatre in the 1830s, and Communist Manifesto authors Marx and Engles spent a lot of time in the area as well. Engels even had his ashes scattered from nearby Beachy Head. There is even a legend that Debussy found inspiration for "La Mer" here. Other famous residents have included The Graduate author Charles Webb, sci-fi writer Angela Carter, occultist Alistair Crowley, comedian Eddie Izzard, Tommy Cooper and many more. Some even say that John Cleese came up Fawlty Towers after a terrible holiday in Eastbourne. Eastbourne Bandstand is one of the town's iconic postcard features, sporting a turquoise blue dome designed with a fusion of oriental and neoclassical design. We saw a placard next to the bandstand commemorating one of the musicians who had gone down on the Titanic. He was member of the quartet that continued to play as the ship sank. It sent chills down my spine, since my Hungarian great-grandfather missed his connection in Hamburg to catch the "unsinkable" ship. He sailed to New York on the Carpathian - the ship which picked up the survivors. Eastbourne is a curious box of contradictions that has many surprises to give. Parts of it might be run down and even dodgy, but the rest is a picture postcard resort of classic British seaside charm. There must be something in its sea air to continuously attract curious and famous characters. *The closest I have to a hometown. Innovation, Contradiction and Modernity - Encountering the 30s with the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid1/4/2013  This article was previously published on Kunstpedia. The exhibition is running until the 7th of January 2013, so you have a few days to still catch it. The volatile decade of the 1930s saw the rise of totalitarian regimes and the advent of the Great Depression, while advances in film and photography offered artists the opportunity to explore new art forms and medias of communications. It’s impossible generalise the 1930s, since as an era it’s represented by eclecticism and contradiction, where art became a complex debate between totalitarianism and individualism; realism versus abstraction; and where nationalism took on international collaboration. The 1930s inherited the artistic fever for experimentation from the previous decades of the 1910s and 20s, however the 30s can be viewed as a time when avant-garde and modernity went their own separate ways under the imposed political and economic climate. The Modern was perceived as individualistic and went against the collective identity imposed by the dictatorships in Europe. Yet, the rise of new advances in photography, publishing and poster art gave artists the chance to break away from the status quo, inspiring innovation and continued experimentation in the world of art. Debates rose up on abstraction and realism, while surrealism expanded on an international basis. The “isms” blended together in an international melting pot where artists like Pablo Picasso took a playful approach to combining styles. The exhibition on display at the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid takes us on a journey back to the 1930s. Like its era, the exhibition is eclectic and extreme, revisiting this fascinating time through the innovation and creativity that gave birth to abstraction, surrealism and new forms of expression through photography and film, while acknowledging the influence the era’s politics. Artists of the 1930s showed the world they had the ability to challenge, aggravate and provoke the conventional order. We’re introduced to the artistic scope of the 1930s through the channel of realism, a broad artistic movement that encapsulated the “New Vision” through to the rise of social realism. Realism became an artistic device used to communicate en masse with the public. It expressed a desire to reach out to broad audiences, resulting in increased eclectic depictions of the style from the photographic impressions like Josep de Togores’s “Group around the Guitar. L’Ametlla de Vallés,” to those with a more experimental edge like Antonio Berni’s “New Chicago Athletic Club” or Philip Guston’s “Mother and Child”. Realism sought to bring art into a public sphere, and despite its name, it refers to an orientation in art rather than an aesthetic connection to reality. Naturalism, a style used to convey “realistic” forms in art as seen in the 19th century, is not a branch of realism. Whether seen in the canvases of the exhibition or in photographs of realist murals from Mexico or the Soviet Union, we see that realism isn’t an aesthetic concept, but rather an ideological one that expresses “true values” such as a social preoccupation with daily life in the interwar-war period. Pursuing the experimental spirit of modernity of the prior decades, the perseverance of abstraction in the 1930s as a form of creative research and expression transformed this innovative art form into a conversation on utopian reflection, form and even politics. Abstraction not only challenged perspectives on the use of form and colour in art, but also considered dimensional space by playing with textures and solid objects imposed on canvas. Laszló Moholy-Nagy’s “AL6 Construction” is a three dimensional composition of oil on aluminium. The forms in Moholy-Nagy’s abstract construction demonstrate interplay of texture and depth; circles of oil paints are contrasted against circular holes, whose depth is emphasised by the aluminium sheet that’s offset from the background. Abstraction in the 30s also became a play of form and colour, sometimes with a regression to childlike naivety as seen in the canvases of Joan Miró to the carefully crafted compositions of Wassily Kandinsky. “Succession” by Kandinsky, demonstrates the artist’s fascination with geometry and colour, where his forms display a mathematical progression of pictorial music as the notes explode into colour on the canvas. Paul Klee’s “Halme (Straw)” also imitates a musical language through paint in his own position on abstraction. While Europe saw the imposition of realism by authoritarian regimes, that considered abstraction as “bourgeois” and “individualistic,” a transatlantic dialogue between European abstract artists, such as Moholy-Nagy and Kandinsky, and artists in the United States was taking place. Across the Atlantic, abstraction was embraced as a visual language not only for private experimentation, but also for public commission, and even though many critics and members of the public favoured realism abstraction grew in popularity, flavouring modern art for decades to come. While surrealism met with significant criticism and even disdain from art critics such as Clement Greenberg in the US, the movement exploded at an international level in the 1930s. While it began as an underground movement with left wing politics, thanks to Salvador Dalí surrealism was ushered into the mainstream and would leave a lasting impact on modern art and popular culture. Through an expanding print and media culture, surrealism embraced modern technology with an ever-growing medium of surrealist photography with artists such as Man Ray. Surrealism was also fused to other movements such as abstraction or even realism, as seen in the works of Pablo Picasso and Joan Miró. Picasso’s “Le Sauvetage,” whose unique perception propelled the artist beyond the cubist styles of his earlier career into his own individual brand of surrealism, whereas Miró’s “Deux Baigneuses [Two Bathers]” is a marriage between surrealist composition and abstract style. On display, you’ll find “pure” surrealist works, such as Salvador Dalí’s “Sketch for the work ‘The Invisible Man’,” and “Surrealist Composition, Fraud in the Garden,” by Yves Tanguy, whose distorted forms and elongated shadows on a deserted plane expresses the classical aesthetics of surrealist painting. While print photography and film reeled in the world of the avant-garde in the 1920s, in the 1930s this new and exciting medium became the gateway to the masses for many artists. While the 1930s saw works of experimental photography rise up in the art world, especially in surrealist circles, many photographers such as Man Ray entered the mainstream by working with fashion magazines like Vogue. Photography served not only as an artistic medium for design and propaganda, but captured the spirit of the decade through themes of applied psychology and the search for non-traditional forms. Many artists turned to the art of the photomontage and photocollage as an alternative form of expression to connect with the public. The display at the Reina Sofia also discusses the use of public space and exhibitions in the 30s. The dictatorships of the totalitarian regimes that dominated European politics acknowledged the importance of art and culture. The theatrical and monumental dominated the European landscape where buildings and public spaces took on a new symbolic meaning; they became an opportunity to inspire ceremony and nationalism among the people. The rise of new technologies also changed the way space was used, with the rise of the science and art of projecting light onto a building to creative light shows. But it was not only illumination that gave exhibitions multimedia feel, sound and film also became an important part of the display. The exhibition spaces of the 1930s saw the rise of world fairs and large-scale exhibition halls, where the exhibitions played to local political and economic climates. Exhibitions became a marriage between fiction and fantasy, and like the spirit of the 1930s were full of contradictions and extremes. Themes of hand made versus the machine; miniature versus the monumental; industrial versus the primitive; individual versus the collective and democratic versus totalitarianism. Through paintings, murals, tapestries, posters and postcards, we can see through the Reina Sofia “Encounters with the 1930s” how the exhibitions of the decade merged the larger than life with the everyday world. One factor crucial in a conversation on the 1930s, especially in Spain, is the effect of the Civil War. The exhibition is structured round Picasso’s iconic “Guernica” painting, which celebrates its 75th anniversary. Spanish artists were active participants in the creative world of the 1930s, and with the rise of the Civil War many artists were exiled either by choice or by force.

The Civil War’s influence on art manifested in different ways. Many artists used realism an idiom to document the events and horrors of the war, through realism many artists could include an emotional dimension into their paintings that photography could not, turning these works into historical archives. Although, the use of art to record horrific acts of war wasn’t limited to realism. Picasso’s “Guernica” conveyed the atrocities of war through stylised form, yet the symbolic and emotional effect the painting has immortalised the tragedy and the horror that took place in the small Basque village of Guernica. The Civil War turned many artists towards the concept of violence as a narrative, some drew stimulus from the conflict, while others joined ranks to do something about the war, inspiring a huge cultural and creative production in Europe and America, both by Spanish exiles and their supporters. To summarise the impact the 1930s had on art is futile, it’s a complex decade that spawned some of the most innovative works of the 20th century. Fully understanding art of the 1930s is one that will require a lifetime of study, but the exhibition leaves you with an impression, a feel for a time when the world was on the edge between war, economic depression, new technology and globalisation. I would like to offer a very special thank you to Milena Ruiz and the staff at the Reina Sofia Museum for their help in preparing this article. References: Exhibition Catalogue: Encounter with the 30s, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia and La Fabrica (2012) The German city of Darmstadt rarely makes it onto the tourist route. This is understandable, since from a afar it just looks like your average German industrial town, but upon closer inspection you'll find it's rich in cultural curiosities and sites. I used to work at the particle accelerator (GSI) located nearby, so I know Darmstadt pretty well. While I lived in Frankfurt, I often travelled to Darmstadt since all my friends from work lived there, which meant I went out in Darmstadt more than in Frankfurt. Even when I moved to Spain, I returned to GSI and Darmstadt on a regular basis for my work, and until I gave up my career in physics, I made at least one or two trips a year. Darmstadt is a fascinating city and it has most certainly earned its title as "the City of Art and Science." With two particle accelerators (GSI and the recently constructed FAIR on the same grounds), the German site for the European Space Agency, the industrial centre of the German pharmaceutical industry (with big companies such as Merck basing their main plants here), it's easy to see why Darmstadt has earned it's scientific wings. Not to mention the city has a chemical element named after it: Darmstadtium (atomic number 110, which was discovered in GSI in 1994). On the arts side, Darmstadt is also home to the former Artists' Colony, Mathildenhöhe. Artists from the German Jugendstil movement both lived and worked in this community. The artists were financed by patrons while they worked together with other members of the collective. Darmstadt Artists' Colony is not just a movement in the history of German Jugendstil, but it also refers to the modernist buildings left behind. From the exhibition hall to the houses artists houses, Mathildenhöhe's modernist architecture has put Darmstadt on Europe's map of art nouveau cities. Darmstadt's avant-garde doesn't stop there. Austrian architect Friedensreich Hundertwasser's Waldpirale is also hidden away in this small, industrial city. Darmstadt might have earned its title as the city of art and culture, so what specifically should you see? If you're staying in nearby Frankfurt, then Darmstadt is just a short train ride away. If you're looking to get out of the city and away from Mainhatten's high-rises, it makes a nice escape. Or, if you're travelling down towards Heidelberg, Darmstadt is a great place to break the journey. Visiting the center of Darmstadt will take you to the area surrounding Luisenplatz. This is the largest square in the city, and it's also the central hub for any public transportation. You'll find many shops and restaurants in this pedestrianised area, but it's also easy to navigate the city from here. Many of the monuments are walking distance from Luisenplatz, such as the ducal palace of Darmstadt. This was once the palatial residence of the counts of Hesse-Darmstadt, and then the Grand Dukes of Hesse. The palace's look stems from its 18th century refurbishment and additions, but the castle itself actually dates back to the 13th century. Opposite the square is the historic Marktplatz. Facing the front of the ducal palace is the old town hall, which now houses a tavern. The "Ratzkeller" (link in German) serves its own beer (there is a brewery in the basement) and traditional food from the Hessen region. It sports a cosy atmosphere and bags of character, not to mention the high quality food and delicious selection of wheat beers. The Artists' Colony in Mathildenhöhe is a little out of town, but worth a visit. Here you'll find the iconic five fingered "wedding tower" which has become a symbol of the city. In addition, there is a Russian chapel and a number of the artists' houses in the Jugendstil style. The colony was founded at the end of the 19th century by the Grand Duke of Hesse, Ernest Ludwig. Mathildenhöhe was created by Ludwig to promote the art scene of the Hessen region, helping to combine trade and art so it would act as an economic stimulus for the land. Artists housed in the colony sought to develop the modern and avant-garde into a way of living and construction. As a result, Ernest Ludwig brought many of Germany's top Jugendstil artists to live in Darmstadt, such as Peter Behrens, Paul Bürck, Hans Christiansen, Rudolf Bosselt, and more. A short walk from Mathildenhöhe is Hundertwasser's surreal Walspirale. Hidden away between allotments, concrete block apartments and an Aldi supermarket, this is hardly a prime location. The Hundertwasser House in Vienna is famous, and always full of tourists. When I visited the Austrian capital it was marked on my list of key things I had to do while I was there. The Hundertwasser House was stunning, a modern-day rival to the modernist buildings of Barcelona, yet the Waldspirale in Darmstadt is even more spectacular. It's downfall is that it's hidden away in Darmstadt's uglier outlying neighbourhoods. Darmstadt is an attractive destination for those looking to immerse themselves in the German countryside. The nearby Bergstrasse (part of the larger Odenwald), a chain of low mountains that run between Darmstadt and Heidelberg, offers stunning hikes. The rolling mountains of the Odenwald are rich in woodlands, vineyards and are dotted with historic, ruined and romantic castles. The most famous, Castle Frankenstein, is located in Darmstadt's suburbs. Legend has it Mary Shelly drew inspiration for her novel Frankenstein after a trip to the to the region. Whether this is true or not is another matter.

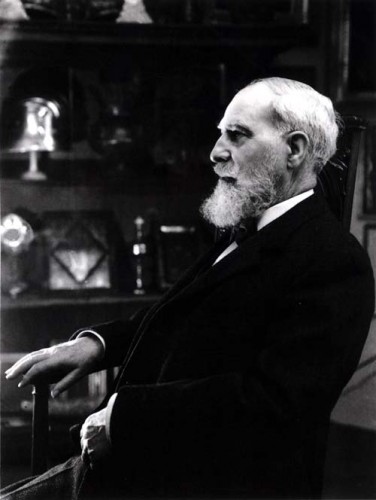

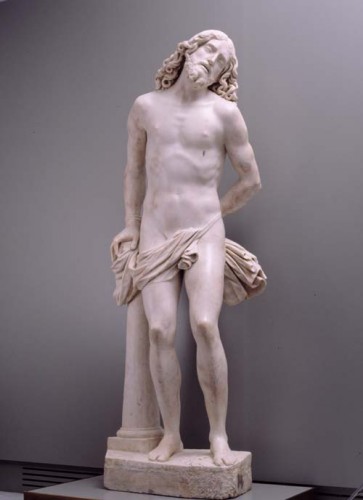

Looking beneath the surface, Darmstadt has a lot to offer any traveller interested in science, art history or even Gothic literature. Find more information about Darmstadt here!  This article was originally published in December 2012 (a year ago to the day, actually) on Kunstpedia. Madrid’s status as one of the great art capitals of Europe’s stems from the big three – the Prado, the Reina Sofia and the Thyssen-Bornemisza. While these museums are undoubtedly spectacular and have rightly earned their status as some of the world’s best, no art lover should bypass the smaller and lesser-known galleries Madrid has on offer. The Museo Lázaro Galdiano is one of the most underrated art museums in the Spanish capital. Located in the beautiful neo-renaissance palace on Serrano Street, it houses the former private collection that had once belonged to José Lázaro Galdiano, a well-known collector and respected bibliophile. Lázaro earned his title as “one of the greatest patrons of culture in 19th century Spain,” and by the end of his life, he not only owned one of the most prestigious art collections in Spain, but had also founded the magazine “La España Moderna” and established a publishing company under the same name. His reputation as a bibliophile developed from his other collecting passion of rare and beautiful antique books. Lázaro’s legacy includes an astounding library filled with works by Goya, masterpieces like the “Hypnerotomachia Poliphili” by Francesco Colonna, “The Polyglot Bible” by Cisneros and some extraordinary examples of Medieval Codices. While access to the library is limited, the Lázaro's renowned art collection is on public display at his former home on Calle Serrano. This palatial residence catches your eye from across the street, and calls you into its garden: Parque Florido, which was named after Lázaro’s Argentinean wife, Paula Florido. The art collection itself is divided amongst the numerous rooms and floors of the palace. The ground floor offers an eclectic mix, covering art from a wide range of eras and countries, and is a preliminary taster for the Lázaro collection. Paintings are hung alongside rare artifacts, like the “Julius Caesar Tazza” dating from the latter half of the 16th century, which had belonged to Cardinal Ippolito Aldobrandini. This dish, adorned with the standing figure of the Roman Caesar, was once part of a series, where each Tazza represented the 12 Caesars from Suetonius. Numerous, quality works of iconographical and symbolic content are found in Lázaro’s collection of Spanish painting, and it is here on the ground floor that we see his love for portraiture emerge. Portraits of Lope de Vega and Góngora adorn the walls, located only a few metres away from Renaissance panels and archaeological artifacts, such as the bronze ewer dating back to the 6th century BC from the ancient port city of Tartassos, now located in Andalucía. The “Treasure Chamber” is a stunning display of precious gold and jewelled items that are housed in the collection, where the Ceremonial Sword, presented to the second Count of Tendilla by the Pope Innocent VIII in the 15th century, is the highlight. These treasures are displayed chronologically: from the gold of the Greeks, Phoenicians and Romans, through to Visigoth and Byzantine, and concludes with the jewels of Paula Florido, Lázaro’s wife. The ground floor offers a glimpse into the collection of European art brought to Spain by Lázaro, showcasing extraordinary and rare pieces that are seldom seen in private Spanish collections. Turning a corner, the 15th century stained glass window depicting St. Michael Weighing Souls, by Antonio da Pandino, grabs your attention. Hung besides it, you can find interesting works sampled from Lázaro’s collection of English paintings, a school rarely found in Spain, such as “The Portrait of Lady Sondes” by Sir Joshua Reynolds. One of the highlights, at least for me, is the moving marble statue of “Christ at the Column” by the Neapolitan sculptor, Michelangelo Naccerino. This life-sized baroque sculpture carved out of white marble contours the delicate details of Christ’s body and draws your eye to his emotive expression. After an introduction to the museum and the collection, the tour continues upstairs. Here the collection is no longer displayed in chronological order, but is instead categorised into schools. The first floor focusses on Spanish art. Chronicling this history of Spanish art was one of Lázaro’s passions. He wanted to preserve a collection which could be used as a reference for the study of Spanish art history. The first floor of the museum is located in the former ceremonial rooms of Lázaro’s family. Here guests would be greeted, and would have even dined and danced. These rooms retain their former splendour, decorated with frescoed ceilings, marbled panels and gold leaf details on the borders. One of Lázaro’s great artistic loves was 15th and 16th century panel painting. From the excellent Gothic and early Renaissance examples on display, it’s easy to see why. The paintings from the traditional Aragonese School follow the traditional Gothic style: where figures are hierarchically positioned and the faces of the saints are idealised. Perspective, as seen from the Renaissance onwards, is missing in these early paintings; instead plain, golden backgrounds dominate, centralising the figures in the painting. The 15th century panel painting by Blasco de Grañen, “Virgin of Mosén Esperandeu de Santa Fe” is an excellent example. The Golden Age of Spanish art, from the 16th and 17th centuries, is well represented— here we see some impressive canvasses by Ribera, El Greco and even early Velázquez. “Saint Francis of Assisi” by Domenicos Theotocopulos, more commonly known as El Greco, is an intimate depiction of the saint. The perfection of his face, hands and skull are painted in his trademark proto-expressionist style combined with loose brush strokes, but it’s the emotional overpowering of the saint's expressive eyes that hook us into this painting. The undisputed stars of Lázaro's Spanish collection are the paintings and cartoons by Francisco de Goya. There are six small canvases, universally acclaimed by critics, but in addition to these, two paintings which have been recently re-attributed to the painter. The most notable Goyas from the collection are “The Witches” and the “Witches Sabbath,” while these canvases are small in size; they capture the sinister atmosphere of their subject matter with the artist’s dark palette and attention to gritty detail. On first glance, the loose brush strokes lull us into a false sense of security before we see in line of baby corpses haunting the background or the emaciated children offered as sacrifice. In their masterful and extravagant execution, these paintings capture conflicting elements of both fear and irony, whose quality put them on par with the Goyas displayed in the Prado. The second floor catalogues the European schools found in the collection. It spans over five centuries and covers not only painting, but also sculpture and the decorative arts. Lázaro’s inclusion of the Flemish and Italian schools complement the collection, as their influence can be directly attributed in the history of Spanish art. One of the most notable pieces is a small portrait, dating back to the late 15th century of “The Young Christ.” Once attributed to Leonardo da Vinci by Spanish critics; art experts eventually concluded that the painting originated from the Lombard School, whose authorship is now attributed to one of da Vinci’s best students, Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio. This panel is believed to be based on one of da Vinci’s designs, and was held in great esteem evidenced by the gilding on the reverse side of the panel. Another gem found in Lázaro’s collection is displayed among the early Flemish panels. “Saint John the Baptist in the Desert,” by Hieronymus Bosch is the highlight of the museum. Here we see St. John reclining in a surreal landscape, where trees are set far into the distance. In the foreground, the saint points to a lamb, which symbolises the road to salvation. What is interesting about this painting is the strange plant set beside St. John. It resembles a deformed pomegranate, interpreted as a symbol for earthly pleasures, but upon closer inspection the pomegranate hides a face. Originally, the patron of the painting was to appear here, however after a dispute with Bosch the artist painted him out and distorted him into a strange looking shrubbery.

The collection continues on the third floor; where we can explore the armoury, antique bronzes and stonework, and most notably, Lázaro’s exquisite collection of textiles. In conclusion, while this small-scale museum dwarfs in quantity when compared to Madrid’s big three, it definitely has the right to stand by them in quality, since it houses pieces that are not only of great aesthetic value, but are significant both for history and art history. If you love art then I can highly recommend a visit to this museum. I would like to give special thanks to Carlos Saguar Quer, for giving me a personal tour round the museum and for teaching me not only about the collection, but also about José Lázaro Galdiano as well, and for all his help and cooperation with this article. References:

So after a very long selection process we're finally getting the new issue out. I've never realised how much work goes into putting together a literary magazine until I got the job with Falling Star. We've received hundreds of submissions over the year, and I've had to read through each one personally before passing them onto my editor. Not to mention writing all the countless, personalised rejections to all those hopeful writers. This is a proper job, but one I've had to juggle with my other writing projects and a day job that takes care of most of the bills. It's a lot of work, but at the end of the day really satisfying. The beautiful thing about literary magazines is that they're labours of love and not (usually) commercial. Literary journals look for quality fiction and poetry, work with literary merit that doesn't necessarily fill a market niche, unlike many publishing houses or magazines. Through working for one, I've really gained appreciation for all the other literary editors out there and their dedication to the work. Last January, I realised why I love this job. We hosted a launch party in Madrid for the spring issue, and we saw turnout of 50 people from Madrid's literary and artistic scene on a Tuesday night. It was a magical experience, one of those which validate why you write. Madrid is a place that has a really active literary scene. If it weren't for their help and support, I would probably still be sitting in an underground lab, analysing data and getting extremely depressed, or perhaps enduring a worse fate, like working in a bank somewhere. Getting this issue out was tough, the editor has been working hard and gaining a lot of success and recognition for his fiction. I was working in Georgia, trying to decide on the fate of my life while reading through submissions, and then I moved back to Spain and resumed my old life. Eventually we realised we wanted to give something back to the writers who contributed and to pay back the writing successes we've had over the year. Here's to a more productive 2013, now that we can't use the end of the world as an excuse anymore. For more details on the magazine, check out our website or our facebook page. |

AuthorJennifer is a freelance writer specialising in art, travel & culture. This blog is a melange of her published articles and independent thoughts. Archives

July 2013

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed